Early Khoisan history

- Early Khoisan history

- https://museumsnc.co.za/new_site/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/early-khoisan-thumb-1.jpg

- ALL CATEGORIES

- https://museumsnc.co.za/new_site/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Early-Khoisan-history-Voiceover_1.mp3

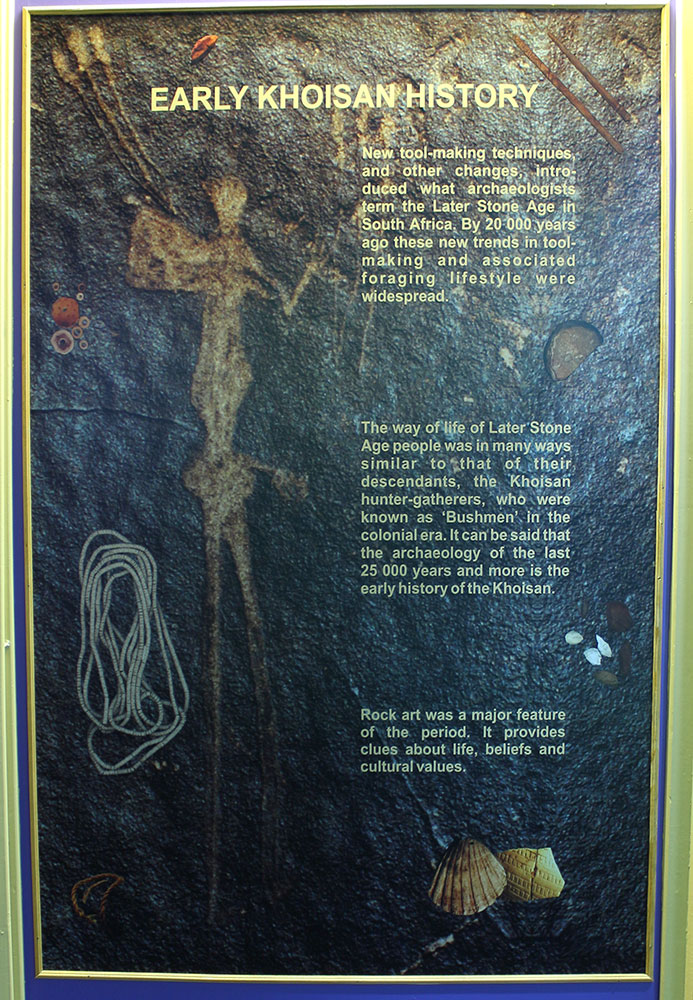

New tool-making techniques, and other changes, introduced what archaeologists term the ‘Later Stone Age’ in Southern Africa.

Traced back to more than 40 000 years, by 20 000 years ago these new trends in tool-making and associated foraging or hunter-gatherer lifestyle were widespread. The way of life of Later Stone Age people was in many ways similar to that of their descendants, the Khoisan hunter-gatherers, who were known as ‘Bushmen’ in the colonial era. It can be said that the archaeology of the last 25 000 years and more is the early history of the Khoisan people, but this should not be taken to mean that it was an era of limited change. On the contrary, there is evidence of dynamism and innovation, with complex regional social and material culture patterning as people engaged with diverse environments. Rock art – both paintings and engravings – was a major feature of the period, providing clues about beliefs and cultural values. Artefacts, generally better preserved than those of earlier periods, were made not just from stone, but also from other materials such as wood, bone, leather, plant fibre, and ostrich eggshell. ‘Microliths’, or small stone tools, such as ‘scrapers’, were used to prepare skins, while ‘blades’ and ‘segments’ were for cutting or mounting as arrowheads.

Later Stone Age hunter-gatherers (some of whom took up herding in the last 2000 years) were descended from earlier Southern African populations. The anthropological term ‘Khoisan’ refers to people who, in the colonial era, were called, pejoratively, ‘Bushmen’, and those named ‘Hottentots’. In recent centuries Khoisan lived generally in herder clans, or small hunter-gatherer groups or bands, speaking a variety of click languages.

The Khoikhoi used the term ‘San’ for people who had no livestock – cattle or sheep. To the Tswana they were ‘Masarwa’, while ‘Bushmen’ was a name given to them by European colonists. The names of Khoisan groups in the centuries and millennia prior to the colonial era are not known. But in recent times different groups knew themselves by names such as |Xam (hunter-gatherers in the Karoo) or ‡Khomani (a group in the southern Kalahari).

Later Stone Age people lived by foraging – collecting plant foods and honey, snaring and hunting animals, and fishing. Wild plant food and animal remains are evidence of what people were eating. Tool ‘kits’ reflect how food was obtained and prepared. Hunters used the bow and arrow over at least the last 20 000 years. Pastoralism was introduced by a combination of migration and local adoption in the last 2000 years. Herding and pot-making was adopted by erstwhile hunter-gatherers in some areas.

In 1811 the traveller William Burchell noted a method of hippopotamus trapping on the banks of the Vaal River: he wrote that, “The vicinity is inhabited by Bushmen, whose pits for ensnaring game were everywhere to be seen…the interval from one to another was crossed by a line of large branches…opposite [each opening] was a deep pit, so carefully covered over with thin twigs and grass… Many of these holes were dug exactly in the paths made by the hippopotami…” He continued, “a hippopotamus had lately been caught and eaten; and the remains of some Bushman huts close by, and probably erected only for the occasion, showed how determined they were to enjoy the feast. Since not being able to carry the meat to their houses, they had removed their houses to the meat.”

When hunter-gatherer bands came together at certain seasons, items of material culture were exchanged, possibly as gifts among kin. Modern !Kung San of the Kalahari call this exchange of gifts hxaro. Seashells from sites in the Northern Cape interior could have come inland through several hxaro exchanges. The traveller Burchell, near the Vaal River in 1811, wrote that: “Several of [the Bushmen] wore two or three cowries interwoven with their hair. On enquiring whence these shells had been procured, I could get no further information than that of their having been obtained from their neighbours by barter.”

At Witsand in the Northern Cape, the geologist and writer George Stow recorded the following in 1873: “I could not help noticing the remarkable regularity and nicety with which the [young women’s] faces were painted. The eyebrows were darkened with straight thick lines of shining black paint, while from either angle of the eye to a point on the cheek, a little below the level of the ear, the face was ornamented with red ochre. The girdles of these women and the ornaments they wore on their heads were made of beads, manufactured by themselves out of ostrich egg-shell. Their aprons were made of numerous thin pieces of twisted leather, ornamented with beads of the same kind. A skin mantle or ‘kaross’, together with bracelets, armlets and anklets completed their attire.”

In the last 2000 years, new herding and farming lifestyles appeared in Southern Africa. It is possible that the idea of herding spread initially by diffusion, with a later migration of Khoikhoi-speakers. Agriculture was introduced by Iron-Age farmers ancestral to Bantu language speakers. Khoisan known as San (by Khoikhoi) or Sarwa (by Tswana) continued to live as hunter-gatherers alongside herder and farmer societies in some areas.