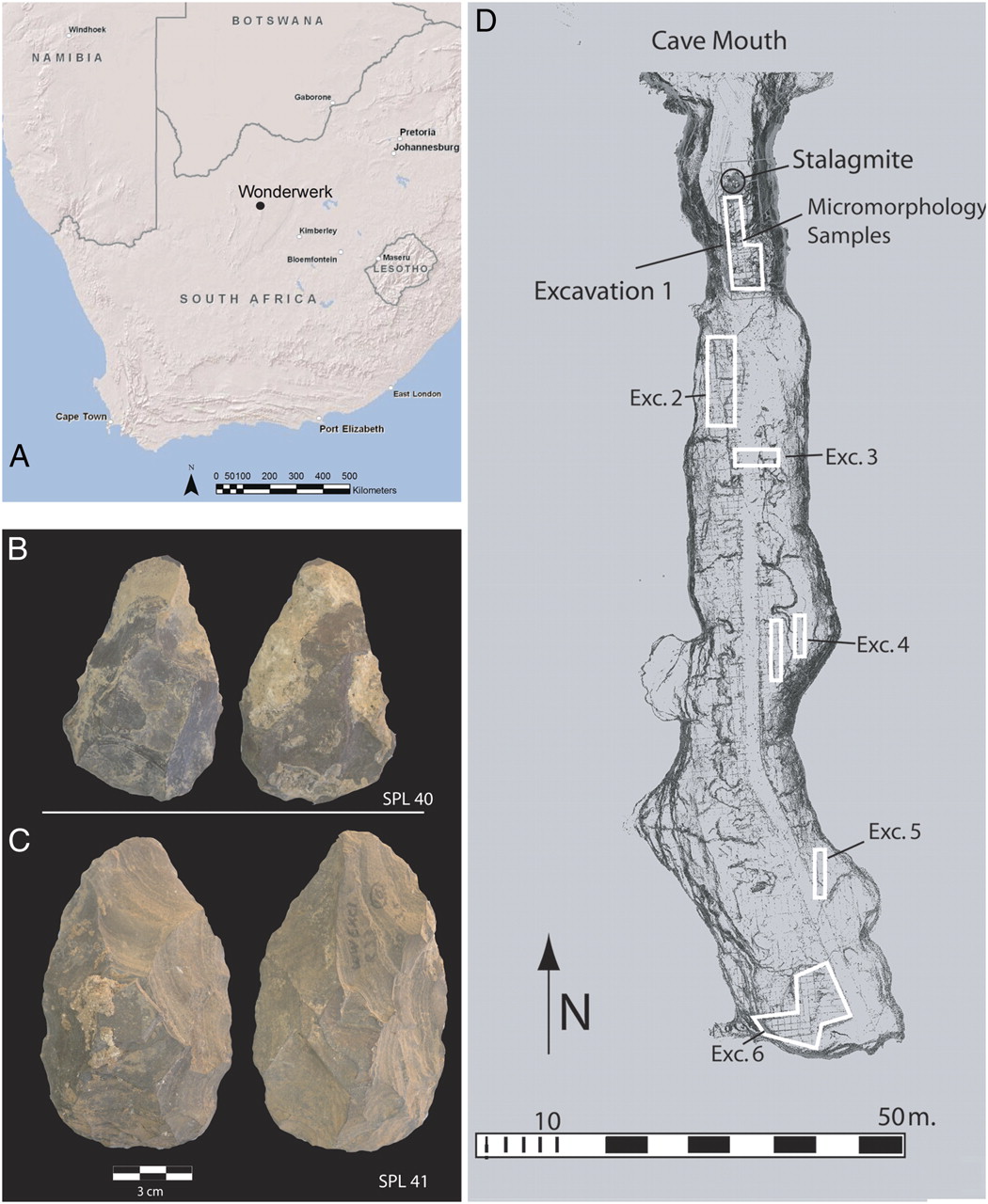

Wonderwerk means Miracle. It is an apt name for a cave which is not only an extraordinary place to experience but is also unique in its geological, archaeological and historical aspects.

Before entering the cave, look at the rocks of the Kuruman Hills. The cave is in dolomite rock that underlies the Banded Ironstone Formation. The dolomite formed in a shallow ocean over 2 billion years ago. The rock contains stromatolites, some of the earliest traces of life on earth. Tube-like solution cavities such as this then formed underground in the dolomite rock, which is soluble. In this instance it has been opened at one end by erosion over millions of years.

When you enter the cave almost the first thing you see is a massive stalagmite which has formed from water dripping through the dolomite above, depositing calcium carbonate. This stalagmite began to grow about 35 000 years ago and is still growing today.